|

|

|

|

FOREWORD

EST you forget the three hundred and sixty-six days spent as a part of the American Expeditionary

Forces, and in a sincere effort to help you call to mind, in the “Years and Days” to come, the

experiences which came your way while helping “Uncle Sam” put the skids to Kaiser “Bill”, this

publication has been brought about. If at any time you happen to glance through its pages and find

something about which you had forgotten, then our mission will have been fulfilled.

L

|

|

DEDICATION

O our joys and sorrows; to our ups and downs; to the friendships formed and the fellowship

experienced; to the days of hardship; to the memory of things we can never forget.

This volume is respectfully dedicated.

T

|

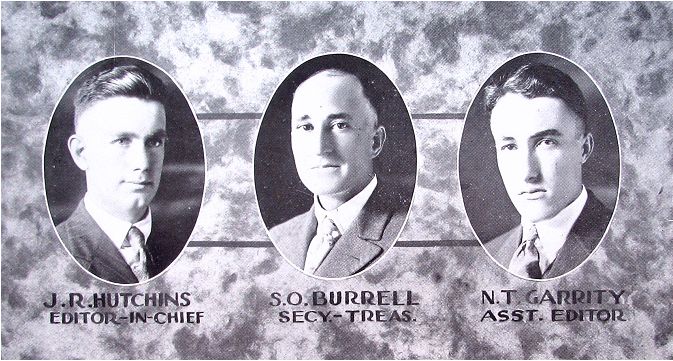

January 14, 1919, the company having been called together by Captain Millender, and it having

been explained to the assembly that it was necessary that a permanent staff should be selected in order to

handle the publication of the company book in a business-like manner, 1st Sgt. Norbert T. Garrity was

chosen as temporary chairman. The following staff was elected and given full authority in the

publication of the book:

EDITOR

SGT. JOHN R. HUTCHINS

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

1st SGT. NORBERT T. GARRITY

SECRETARY AND TREASURER

SGT. SIMPSON O. BURRELL

The funds in the hands of Captain Millender were turned over to Sgt. Burrell, duly receipted for,

and the meeting then adjourned.

|

^&ROSTER

CAPTAIN J. E. L. (LINDY) MILLENDER

CORSICANA, TEXAS

Captain Millender is the man who put A. & M. College on the map in Texas. He became famous

there as one of the best yell leaders said college has ever produced.

He entered the First Officers Training Camp at Leon Springs, Texas, in spring, 1917. He was

later transferred to the Engineer Officers Training Camp at Leavenworth, Kansas. After a short course

of instruction there he was commissioned First Lieutenant. He was then ordered to Camp Travis and

assigned to Company “A” 315th Engineers. He has been with the company since its organization.

Shortly before our departure for overseas, Lieutenant Millender became Captain Millender to the

gratification of all who knew him.

As our Commanding Officer for thirteen months, Captain Millender emulated the high principles

demanded by such a position. Every one of us consider him as a friend for he was never a hard

taskmaster. He expected so much from a man and no more. One of the best traits of his character is the

manner in which he always stood up for his men. He would not, under any circumstances, allow anyone

to hand us something “shady.” Captain Millender was one of the most popular officers in the Regiment.

|

MAJOR H. R. COOPER – Commissioned Captain in Engineer Officers Training Camp at Leavenworth,

Kansas, in summer, 1917. Assigned to Camp Travis; later to 315th Engineers. Commanded “A”

Company for a few weeks in Spring of 1918; received Majority shortly prior to our departure overseas

and was made Commander of the First Battalion, 315th Engineers. Remained in this capacity until

appointed Athletic Officer for 90th Division in January, 1919. Welfare Officer for Third Army since

February, 1919.

CAPTAIN R. W. BAKER – Commissioned First Lieutenant in Engineer Officers Training Camp at

Leavenworth, Kansas, in Summer of 1917. Assigned to 315th Engineers and later to “A” Company.

Remained with us until appointed Assistant to Division Engineer in February, 1919. Promoted to be

Captain Engineers, in April, 1919. Remained in France as assistant in office of Chief Engineer, Paris.

FIRST LIEUTENANT P. M. NICOLLET – Commissioned First Lieutenant in Engineer Officers

Training Camp at Leavenworth, Kansas, in Summer of 1917. Assigned to 315th Engineers, “B”

Company. Joined “A” Company a few days prior to leaving Camp Travis. Received Divisional Citation

for work in St. Mihiel offensive. Transferred to 30th Division in January, 1919.

FIRST LIEUTENANT THOS. G. GAMMIE – Commissioned Second Lieutenant in Engineer Officers

Training Camp at Leavenworth, Kansas, in Summer of 1917. Assigned to 315th Engineers, Company

“A.” Promoted to be First Lieutenant in October, 1918.

|

|

FIRST LIEUTENANT J. S. WATERS. JR. – Commissioned Second Lieutenant in Engineer Officers

Training Camp at Leavenworth, Kansas, in summer of 1917, and assigned to Company “A” 315th

Engineers. Promoted to be First Lieutenant in November, 1918, at Stenay, France, and transferred to

“D” Company.

FIRST LIEUTENANT VIVIAN J. LEWEY – Commissioned Second Lieutenant in Army Candidates

School, Langres, France, in October, 1918. Later promoted to be First Lieutenant and assigned to “B”

Company 315th Engineers. Transferred to “A” Company in April, 1919.

SECOND LIEUTENANT H. R. LINDBLOM – Commissioned Second Lieutenant at Army Candidates

School, Langres, France, in October, 1918. Assigned to Company “A” 315th Engineers in October,

1918. Town Major at Daun for several months.

SECOND LIEUTENANT H. E. SNOW – Commissioned Second Lieutenant at Army Candidates

School, Langres, France, in October, 1918. Assigned to Company “A” 315th Engineers, and ordered to

Third Corps School at Clamercy, France. Rejoined Regiment in January, 1919.

SECOND LIEUTENANT W. E. BOGER – “Buck,” Corporal. Sergeant and Supply Sergeant in

Company “A” 315th Engineers until ordered to Army Candidates School, Langres, France, in October,

1918. Received Certificate of Eligibility for Commission as Second Lieutenant December 1, 1918.

Commissioned in April, 1919, and attached to “D” Company.

SECOND LIEUTENANT R. W. HINTZ – Sergeant 1st Cl. in “C” Company when sent to Army

Candidates School, Langres, France. Received Certificate of Eligibility for Commission as Second

Lieutenant on January 1, 1919. Commissioned Second Lieutenant in April, 1919, and attached to “A”

Company.

SECOND LIEUTENANT GLEN H. HESS – Corporal in Headquarters Company when sent to Army

Candidates School, Langres, France. Received Certificate of Eligibility for Commission as Second

Lieutenant on December 1, 1919. Commissioned Second Lieutenant in April, 1919, and attached to “A”

Company.

|

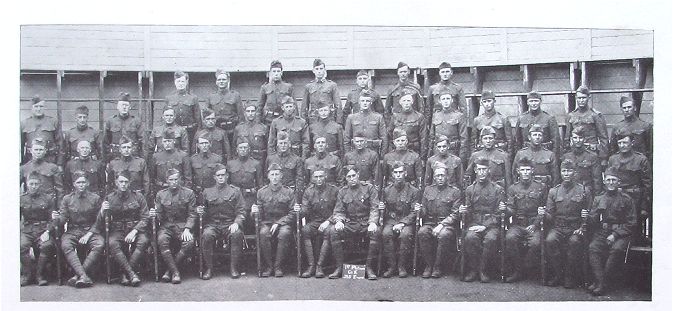

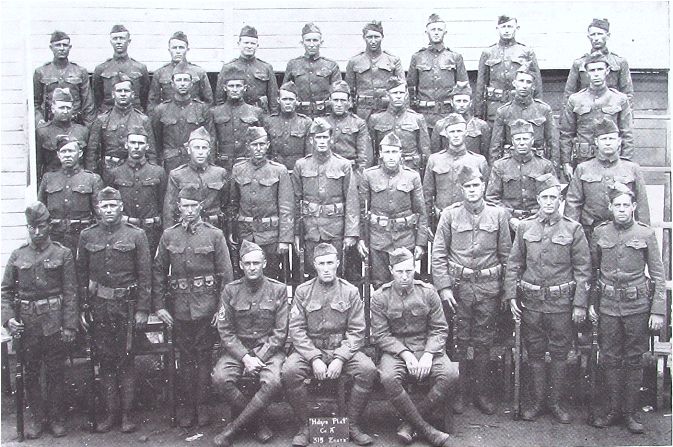

FIRST PLATOON

Top Row – Left to right – Pvt. Elam, W.; Pfc. Cox. W. C.; Pvt. Lamb, C. R.; Pfc. McGraw, J,;

Pvt. Morris. H. E.; Pvt. Jensen, H. W.; Pvt. Hagen, E. O.

Second Row – Pvt. Metzler, C. C.; Pvt. Boehm, H. J. ; Pvt. Romer, C. L. Pfc. Schmidt, J. H.;

Pvt. Bembenek, W. ; Pfc. Canepa. S.; Pfc. Gaston. J. A.; Pvt. Ewing. C. ; Pvt. Anderson, M. A. Pvt.

Thome, A. M.; Pvt. Trout, C. L.; Pvt. Wood, Cleo; Pvt. Warfield. A.; Pvt. Revill, A.; Pvt. D’Alessandro,

A.

Third Row – Pvt. King, C.; Pvt. Skordahl, O.; Pfc. Thomas, C. C.; Pfc. Haladej, V.; Pfc. Jones,

H. H.; Pfc. Anderson, H. A.; Pfc. Gilbert. W.; Pvt. Fisher, E. A.; Pvt. Johnson, L. W. ; Pvt. Wilkie, S.

C.; Pvt. Hollingsworth, W. B.; Pvt. Petrillo. A.; Pvt. Lodien, A. L.; Pfc. Olson, E.; Pvt. Marcotte, M.

Bottom Row – Cpl. Dogila, A.; Cpl. Walton, W. F.; Cpl. Carmichael, E.; Cpl. Schlichting, C.;

Cpl. Harrison, C.H.; Sgt. Williams, J. A.; Sgt. Boazman, A. S.; Sgt. 1Cl. Sartain, J. C.; Sgt. Hardaway,

W. L.; Cpl. Minor, R. N.; Cpl. Ellickson, W. A.; Cpl. Barton, N.; Cpl. Savage, R.; Cpl. Crawford, J. E.

|

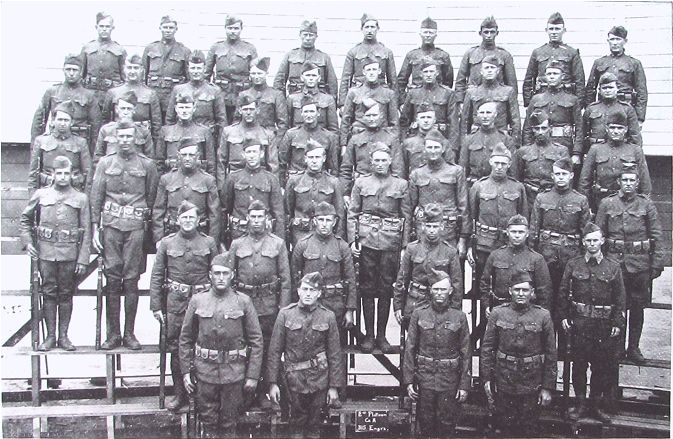

SECOND PLATOON

Top Row – Left to Right – Pfc. Hansen, A. B.; Pvt. Erickson, A.; Pvt. Clearwater, G. D.; Pvt.

Anderson, P. J.; Pvt. Milostan, E. G.; Pvt. Lokka, P.; Pvt. Hanson, N. A.; Pvt. Jester, G. D.; Pvt.

Williams, D. J.

Second Row – Cpl. Jackson, A. D.; Cpl. Brennan, F. M.; Pvt. Tweedt, O. J.; Pfc. Barrett, D. L;.

Cpl. Mueller, H. L.; Pfc. Stebbins, J. D.; Pvt. Dunn, D. A.; Pvt. Waye, L. B.; Pvt. Leutwyler, E. T.; Pvt.

Brumit, E.

Third Row – Pvt. Hughes, T. N.; Cpl. Groom, C.; Pfc. Jones, L. B.; Pvt. Krings, A. J.; Pvt.

Farms, C. F.; Pfc. Gillogly, L. M.; Pfc. Thompson, W. O.; Pvt. Potosnak, J.; Pfc. Oquin, S. J.; Pvt.

Gillett, J. E.

Fourth Row – Pvt. Marino, N.; Pfc. Schroeder, H.; Pfc. Cromer, A. L.; Pvt. Bellefontaine, G. H.;

Pfc. Carlson, C.; Pvt. Fisher, L. S.; Pvt. Rossman, R. E.; Cpl. MyFarlin, A. U.; Cpl. Scott, V. M.; Pvt.

Opdyke, E. J.

Fifth Row – Cpl. Heins, F. C.; Pfc. Toller, O. E.; Pvt. Juras, J.; Pvt. Nickelson, I. I.; Pfc. Redi,

C.; Cpl. Dennis, R. T.

Bottom Row – Sgt. Robards, F. A.; Sgt.1Cl. Duke, J. C.; Sgt. Donham, R. L.; Sgt. Duckworth, F.

M.

|

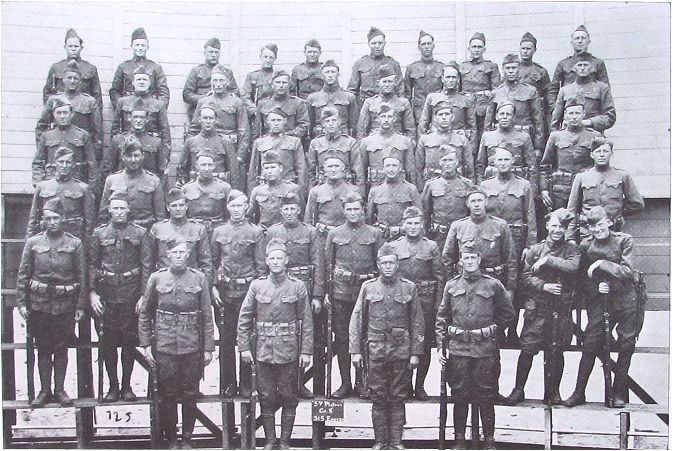

THIRD PLATOON

Top Row – Left to Right – Pfc. Wimberly, R.; Pvt. Nygren, F. W.; Pvt. Graham, T. P.; Cpl.

Fayle, J. J.; Pvt. Dickens, C. F.; Cpl. Daly, J. F.; Cpl. Archer, F. L.; Pvt. Lieuellen, A. C.; Pfc. Davies, T.

W.; Pvt. Edler, H. H.

Second Row – Pfc. Hartman, F.; Pvt. Johnson, C. H.; Pvt. Borg, J.; Pfc. Snyder, H. O.; Cpl.

Mathiews, J. C.; Pvt. Holland, M. J.; Pvt. Waddill, F. V.; Cpl. Findeisen, A. H.; Cpl. Mackey, H. W.

Third Row – Pvt. Qualizza, M.; Pvt. Coen, D. E.; Pvt. Thompson, C. E.; Pvt. Schmidt, R.; Pvt.

Rizzatti, G.; Pvt. Ingraham, L.J.; Pvt. Marvik, D.; Pfc. Rassmussen, R. C.; Pfc. Kroske, S. J.

Fourth Row – Pvt. Kennedy, S. L.; Cpl. Willims, H.; Pvt. Pearson, G. W.; Pvt. Franklin, C.; Pfc.

Burgess, F. T.; Pfc. Childress, F. H.; Pfc. Lancaster, E. D.; Pvt. McPhillips, G. W.; Cpl. Henderson, W.

E.

Fifth Row – Pvt. Cadle, O. R.; Pvt. Mitchell, H. S.; Pvt. Wesely, J.; Pvt. Stone, P. E.; Pvt.

Farrell, F. L.; Pfc. Gross, N.; Cpl. Blanek, C.; Pvt. Erickson, E. R.; Pvt. Williams, L. R.; Pvt. Antrim, H.

E.

Bottom Row – Sgt. Franks, B.; Sgt. Riker, E.; Sgt. 1Cl. Padgett, E.; Sgt. Burrell, S. O.

|

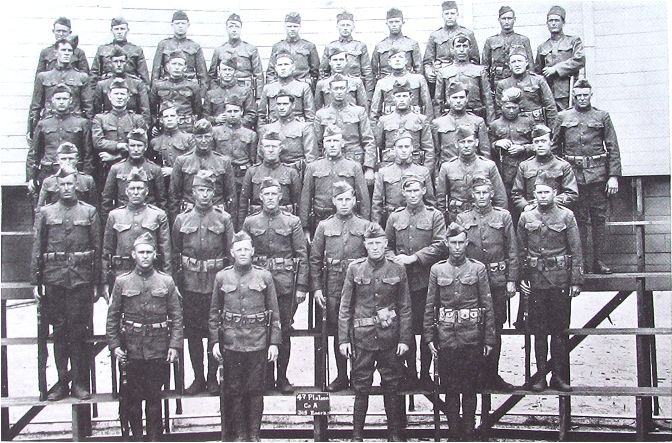

FOURTH PLATOON

Top Row – Left to Right – Cpl. Daly, M. F.; Pvt. McQueen, E. N.; Pvt. Crumbie, W. A.; Pvt.

Redman, P. I.; Pfc. Swanson, J. E. ; Pvt. Gagne, E.; Cpl. Coley, I. G. ; Pfc. Peterson, E. B.; Pvt.

Hollingsworth, B. F.; Pvt. Wilson, R. C.

Second Row – Pvt. Westbrook, W. N. ; Cpl. Kipp, R.; Pvt. Morgan, A. E.; Pvt. Januchowski, F.

J.; Pfc. Johnson, E. A.; Pfc. Lane, E. D.; Cpl. MacDonald, E. P.; Pvt. Eidson, V.; Pfc. Campbell, J. D.

Third Row – Pvt. Liepke, A.; Pfc. Guin, S. H.; Pvt. Caputo, P.; Pvt. Kerner, G. R.; Pfc. Kuhn, N.

M.; Pfc. Wheelock, J. N.; Pvt. Berg, J. A.; Pvt. Arrighini, A.; Pfc. Douglass, M. Y.; Pfc. Clauson, O.

Fourth Row – Pvt. Sekusky, W. J.; Pvt. Tidwell, O. M.; Pfc. Schad, P. A.; Pfc. Johnson, C. G.;

Cpl. Tullis, E. R.; Pvt. Walsh, E. M.; Cpl. Cox, A. W.; Pvt. Gruber, A. O.

Fifth Row – Cpl. Richardson, H. C.; Pvt. Oakley, S.; Pvt. Merila, A. A.; Pfc. Anderson, A. J.;

Pfc. Stefanich, L.; Pvt. Etzel, R. A.; Pvt. Rogers, B. A.; Cpl. Gordon, R. W.

Bottom Row

– Sgt. Dieter, E. G.; Sgt. Anderson, L. H.; Sgt. 1Cl. Donley, J. F.; Sgt. Hilton, W.

H. S.

|

FIFTH PLATOON

Top Row – Left to Right – Pvt. Waldrop, A. E.; Pfc. Leslie, L. H.; Wagoner Wolf, O. C.; Clerk

Sliger, H. C.; Wagoner Wallace, W.; Historian Boldnan, P. C.; Wagoner Gibson, L.; Pvt. Rainosek, J.;

Clerk Enders, O. P.

Second Row – Pfc. Gersch, T. E.; Cpl. Malsch, M. D.; Cpl. Edwards, J. W.; Wagoner Dills, M.

J.; Pvt. Combs, J.; Sadler Johnson, H. M.; Pfc. Farnsworth, J. W.; Pfc. Gersch, W. C.; Wagoner Serrato,

J. ; Cpl. Thomas, J. R.

Third Row – Pfc. Sayre, L. A.; Cpl. Lewis, H. H.; Cpl. Rundberg, D. H.; Wagoner Owens, M.;

Bugler Hensley, O.; Pfc. Maine, W. H.;Wagoner Dunn, D. P.; Wagoner Crenshaw, J.; Clerk Anderson,

J. H.

Fourth Row – Mess Sgt. Noble, J. D.; Sgt. Erickson, C. J.; Sgt. Hutchins, J. R.; Stable Sgt. West,

C. G.; Supply Sgt, Boesling, T. E.; Sgt. Odell, H. W.

Sitting – Sgt. 1Cl. Vance, J. A.; 1st Sgt. Garrity, N. T.; Sgt. 1Cl. Forster, J. H.; Clerk Mosel, W.

A. was on duty at the time above picture was taken.

|

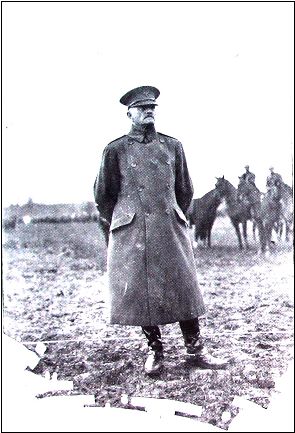

GENERAL JOHN J. PERSHING

General John. J. Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces, next to

President Wilson, represents our idea of the most important man connected with the interests of the

United States during the European conflict. To attempt to eulogize him does not fall in our category. It

is enough to say that we are proud to have been a part of the great army which he commanded; proud to

have had him as our leader, and will always remember him as a great man who played a great part in a

great war.

The picture above was snapped by Captain Millender when General Pershing reviewed the

Ninetieth Division at Wittlich, on April 26, 1919.

|

|

Complete Roster, Company A, 315 Engineers

As of June 15, 1919

OFFICERS

CAPTAIN

J. E. L. Millender

FIRST LIEUTENANT

Thomas G. Gammie

ENLISTED MEN

FIRST SERGEANT

Garrity, Norbert T.

SERGEANT FIRST CLASS

Sartain, Jake C.

Donley, Joe F.

Vance, James H.

Duke, James C.

Forster, John H.

Padgett, Elmer

SERGEANTS

Erickson, Cecil J.

Robards, Frank A.

Burrell, Simpson 0.

Hilton, William H. S.

Hardaway, Weyman L.

Hutchins, John R.

Donham,Robert L.

Franks, Berry

Anderson, Leslie H.

Williams, James A.

Duckworth, Frank M.

Riker, Elmer L.

Dieter, Erwin C.

Odell, Harry W.

Boazman, Alvin E.

MESS SERGEANT

Noble, Jefferson D.

SUPPLY SERGEANT

Boesling, Thomas E.

STABLE SERGEANT

West, Campbell C.

CORPORALS

Crawford, John E.

Dennis, Robert T.

Wilems, Hector

Richardson, Harvey C

Minor, Robert N.

Archer, Floyd L.

Coley, Irwin C.

Walton, William F.

Mueller, Henry L.

Henderson, William E.

Kipp, Robert

Barton, Nolan

McFarlrn, Andrew U.

Mackey, Huel W.

Daly, Maurice F.

Carmichael, Edward L.

Jackson, Arthur D.

Blanck, Carl

Barshop, Sam

Savage, Ross

Hems, Frank C.

Fayle, John J.

Tullis, Earl R.

Ellickson, William A.

|

|

Malsch, Milton D.

Groom, Cales

Mathews, J. C.

Gordon, Robert W.

Schlichting, Charles

Thomas, James R.

Scott, Vernon M.

Findeisen, Arthur H.

MacDonald, Edgar P.

Harrison, Charles H.

Brennan, Frank N.

Rundberg, Donald H.

Daly, James F.

Doglio, Albert

Cox, Andrew W.

Lewis, Henry H.

COOKS

Anderson, John H.

Edwards, Jesse W.

Enders, Oscar P.

Mosel, Walter A.

Sliger, Henry C.

WAGONERS

Crenshaw, John

Dills, Marion J.

Dunn, Doc P.

Gipson, Lee

Owens, Monty B.

Seratto, Jose A.

Wallace, Walker

Wolf, Oris C.

HORSESHOER

Bolduan, Paul C.

SADDLER

Johnson, Roy M.

BUGLER

Hensley, Otto

PRIVATES, FIRST CLASS

Anderson, Anders J.

Anderson, Hildrum A.

Barrett, Don L.

Burgess, Floyd T.

Campbell, Joseph D.

Canepa, Salvatore

Carlson, Gust

Childress, Fred H.

Clauson, Oscar

Cox, William C.

Cromer, Anthony L.

Davies, Taylor W.

Douglass, Malcolm Y.

Farnsworth, John W.

Freeman, William W.

Gaston, Joseph A.

Gersch, Theodor E.

Gersch, William C.

Gilbert, Walter

Gillogly, Lon M.

Gross, Max

Gum, Scott H.

Haladej, Victor

Hansen, Andrew B.

Hartman, Frank

Johnson, Conrad G.

Johnson, Emil A.

Jones, Hilliard H.

Jones, Leroy B.

Kroske, Stephen J.

Kuhn, Edmund M.

Lancaster, Elves D.

Lane, Earl D.

Leslie, Lynn H.

McGraw, James

Main, William H.

Olson, Emil

Oquin, Sevan J.

Peterson, Edwin B.

Ranson, Fred B.

Rasmussen, Robert C.

Riedi, Christain

Sayre, Louis A.

Schad, Phillip A.

Schmidt, John H.

Schroder, Henry

Snyder, Harry 0.

Stebbins, Joseph B.

Stefanich, Louis.

Swanson, John E.

Thomas, Carl C.

Thompson,Walter 0.

Toiler, Otha E.

Wheelock, John N.

Wimberly, Rubie

|

|

PRIVATES

Anderson, Martin A.

Anderson, Peter J.

Antrim, Herman E.

Arrighini, Artel

Bembenek, William

Bellefountaine, George H.

Berg, John

Berg, John A.

Boehm, Herman J.

Brumit, Ed.

Cadle, Oliver R.

Caputo, Pasquale

Clearwater, George D.

Coen, David E.

Combs, John

Crumbie, Watson A.

D’Alessandro, Antonio

Dickens, George F.

Dunn, Drewery A.

Edler, Herbert H.

Eidson, Virgil

Elam, William

Erickson, Axel

Erickson, Erick R.

Etzel, Robert A.

Ewing, Charles

Farms, Carl E.

Farrell, Francis L.

Fischer, Emil

Fisher, Louis S.

Franklin, Claude

Gagne, Ephram

Gillett, James E.

Graham, Thomas P.

Gruber, Arnold 0.

Hagen, Elmer 0.

Hansen, Nels A.

Holland, Malvin J.

Hollingsworth, Ben. F.

Hollingsworth, Warren B.

Hughes, Thomas N.

Ingraham, Lawrence J.

Januchowski, Frank J.

Jensen, Harry W.

Jester, Gordon D.

Johnson, Carl H.

Johnson, Conrad G.

Johnson, Lee W.

Juras, John

Kennedy, John L.

Kerner, George R.

King,Carl

Krings, Anthony J.

Lamb, Clifford R.

Leutwyler, Edward T.

Lieuel]en, Abe C.

Liepke, August.

Lodien, Aleck L.

Lokka, Peter

McPhillips, George W.

McQueen, Elza N.

Marcotte, Matthew

Marino, Nicholas

Marvik, Daniel

Merila, Andrew A.

Metzler, Carl C.

Milostan, Edward G.

Mitchell, Herbert S.

Morgan, Andrew E.

Morris, Hobart E.

Nickelson, Isaac I.

Nygren, Fred W.

Oakley, Stewart

Opdyke, Enos J.

Pearson, Guy W.

Petrillo, Albert

Potasnak, John

Qualliza, Michele

Rainosek, Joseph

Redmon, Pete I.

Revill, Aaron

Rizzatti, Gino

Rogers, Benjamin A.

Romer, Charles L.

Rossman, Roy E.

Schmidt, Robert

Sekusky, William J.

Skordahl, Ole

Stone, Percy E.

Thome, Albert M.

Thompson, Charles E.

Tidwell, Oscar M.

Trout, Chester L.

Tweedt, Osmund J.

Waddill, Frederick

Waldrop, Amos E.

Walsh, Edmund R.

Warheld, Albert

Waye, Leo B.

Wesely, Joseph

Westbrook, Woody N.

Wilkie, Clifford E.

Williams, David J.

Williams, Leroy

Wilson, Robert C.

Wood, Cleo

|

|

|

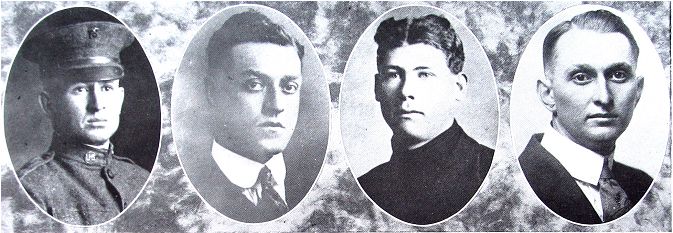

WILLIAM C. JONES LEO J. JAMES

FRED L. DUNSMOOR ERNEST W. MERKLE

Fort Worth, Texas

Buxton, Iowa

Strawberry Point, Iowa

Cissna Park, Ill.

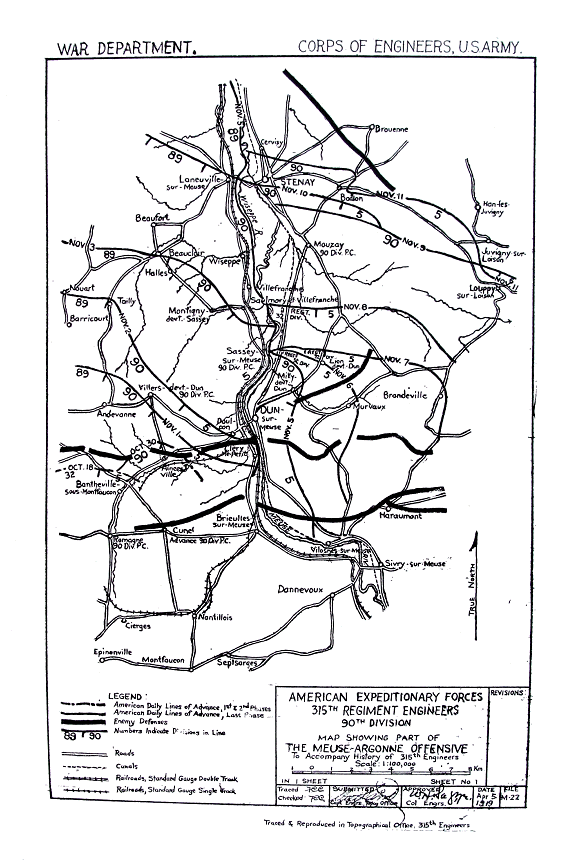

WILLIAM C. JONES, FORT WORTH, TEXAS

Sgt. Jones was one of the original men of Company A. He joined us at Camp Travis, Texas, on

September 19, 1917, and was with us continuously until he met his death near Montigny, November 8,

1918.

Jones was one of the best men in the Company, being always full of pep, willing and energetic.

On the morning of November 8, 1918, he was in charge of a detail repairing the road between Villers-

Devant-Dun and Montigny, about one and a half Kilometers south of Montigny. The road was under

direct observation from the enemy, and was a very dangerous place, subject at all times to bombardment

from a battery of Austrian 88’s concealed in the heights across the Meuse, about three Kilometers

distant. On this particular morning nothing happened until about eleven o’clock, when a Salvo was sent

over. One of the shells hit in the midst of Sgt. Jones’ detail, killing Jones instantly.

He was buried about fifty yards below the road opposite the spot where he met his death.

LEO J. JAMES, BUXTON, IOWA

Cpl. James joined us at Camp Travis during May, 1918, coming from Camp Dodge, Iowa. He

was a quiet man, very efficient, and one of the best workmen we had in the Company.

On the morning of November 8, he was in charge of one squad of Sgt. Jones’ detail repairing

roads and was severely wounded by the same shell which killed Jones and Knox.

When first-aid men reached him, he had dragged himself to the shelter of the bank along the road

and he told them. “Dress the other boys, they’re hurt worse than I am.” It was found, though, that he

was severely wounded, and, after his wounds were dressed, he was placed in an Ambulance and sent to

the Field Hospital.

His death came on the night of November 9th – 10th.

FRED L. DUNSMOOR, STRAWBERRY POINT, IOWA

Dunsmoor was one of the men sent to us from Camp Dodge, Iowa. He joined the Company at

Camp Travis during May, 1918.

He served us faithfully until November 10, 1918, when he was missed. Little is known of his

death. He was last seen on the evening of the 1 0th, while the Company was resting along the National

Highway about two Kilometers south of Mouzay. When the Company was formed he was absent, and

was carried as “Missing” until November 29th, when notification was received from Central Records

|

|

Office that his body was found and interred by a Chaplain of the 360th Infantry, who gave as the cause

of death “Shrapnel.”

His grave is on the outskirts of the town of Mouzay, where his body was found.

ERNEST W. MERKLE, CISSNA PARK, ILL.

Merkle came to us from Camp Dodge, Iowa, during May, 1918.

He was a mighty good soldier – modest, quiet and unassuming; always present when anything

was to be done, and with no kicks to make.

He served with us during the whole of our operations, but in November, 191 8, his health failed

him and he was forced to go to the Hospital.

Nothing more was heard of him until we received notice of his death at Camp Hospital No. 52,

LeMans, France, on January 12, 1919.

Cause of death: Complicated Lobar Pneumonia.

JOHN W. WEATHERLY, GARRISON, TEXAS

Weatherly was one of the original members of the Company, having joined us September 19,

1917, at Camp Travis. He was with us continuously from that time until September 13, 1918, and his

never-failing good humor and willingness not only made of him an excellent soldier, but won for him a

friend in every man in the Company.

On September 13, 1918, while the Second Platoon was taking a few moments rest in the

Stumpflager, north of Fay-en-Haye, preparatory to relaying a load of ammunition to the front lines, the

Germans swept the south side of the valley with artillery fire and Weatherly was hit with a fragment of a

high-explosive shell. He was carried to the 357th Infantry First Aid Station, and from there sent to the

rear. The next word we had of him was a notice of his death aboard a transport November 16, 1918.

Weatherly was the first casualty in the Company.

JASPER B. KNOX, SALINA, OKLA.

Knox came to us from Camp Dodge during May, 1918. His genial disposition, coupled with his

willingness and ability, made him a general favorite with both Officers and Men.

At the front he was fearless and absolutely dependable. He was one of the explosive men who

accompanied Sgt. Duke when they penetrated the German lines and blew up the enemy ammunition

dump.

He was a member of Sgt. Jones’ detail on the morning of November 8th, and met his death from

the same shell which killed Sgt. Jones. Death was practically instantaneous.

He was buried alongside of Sgt. Jones, about fifty yards below the road, and opposite the spot

where he lost his life.

FRANK B. RAY, WALKER, IOWA

Ray joined the Company while we were enroute from the St. Mihiel to the Verdun front, being

one of the first replacements we received.

He was only with the outfit a short time, but proved to be a quiet, willing worker, and was

making numerous friends.

On October 24, 1918, he was one of a detail sent to guard a captured German Engineer Dump

near Nantillois. It happened that an American Field Hospital was right beside the Dump and the

Germans, true to their habits, were shelling this Hospital at intermittent intervals. The shelling on the

morning of the 25th was more intense and covered a greater range than it had previously, and several

shells landed in the Engineer Dump. Ray was killed by one of these shells while in the act of lighting

his pipe.

He was buried in the U. S. Cemetery at Nantillois.

|

|

FRANCIS W. STEELE, BOONE, IOWA

Steele joined us at Camp Travis during May, 1918, being one of the increment from Camp

Dodge sent to fill the Division to war strength.

He was very popular in the Company, and, while we were stationed at Bure-les-Templiers, was

wont to give a nightly concert with his mouth-organ.

On August 20th, he was sent on Special Duty with the Ration Detail, where he served efficiently

until he met his death.

There were no eye-witnesses to his death. He was found near the Red Cross Station at Auberge-

St. Pierre about half an hour after a particularly intense bombardment on October 2, 1918, had ceased.

Death had evidently come instantly, because he still held, clutched in his hand, a bunch of letters which

he had received about an hour previously.

He was buried in the 315th Engineer Cemetery at Fay-en-Haye.

RICHARD A. SWENSON, MELBY, MINN.

Swenson joined us at Camp Travis in May, 1918, being one of the men sent to us from Camp

Dodge, Iowa. He was universally well liked in the Company, and served as Company barber during our

training period in France.

On October 3, 1918, he was a member of a detail under Sgt. Duke, which was sent up to build a

splinter-proof shelter for the Red Cross Station at St. Marie Farm, near Vilcey-sur-Preny. While the

detail was crossing “Death Valley” a German plane swooped down and opened up on them with his

machine gun. Swenson was the only member of the detail who was hit, but his wounds proved fatal in a

few moments. An explosive bullet had entered his right shoulder, ranging downward and exploding in

his left hip. His only words were, “They got me.”

He was buried by members of the Company in the 315th Engineers Cemetery near Fay-en-Haye.

|

|

Headquarters 315th Engineers, American E. F.

GENERAL ORDERS:

No. 124.

18 December, 1918.

1.

The following named officers and men of this Regiment, having been wounded in action

either in the St. Mihiel or Meuse-Argonne operations, are hereby authorized to wear the Wound

Chevron, in accordance with the provisions of G. O. No. 110, GHQ c. s.

2.

Many of the officers and men named hereon have been so seriously wounded as to prevent

their return to the Regt; many, less seriously wounded, are now with us. To all, however, the

Regimental Commander with full knowledge of the spirit with which these officers and men are imbued

extends his compliments and assurance of appreciation:

OFFICERS:

Baker, Ralph W.

1st Lt. Co. A.

20 Sept. 18 Near Fey-en-Haye

ENLISTED MEN

COMPANY A

Cannon, Clement C.

Pvt.

5

Oct., 18 near Fey-en-Haye

Cox, William C.

Pfc.

17

Sept., 18 near Fey-en-Haye

Hedgpeth, James A.

Pfc.

1

Nov., 18 near Romagne

Hollingsworth, Warren B.

Pvt.

27

Oct., 18 near Romagne

Keeble, Walter E.

Sgt.

5

Nov., 18 near Montigny

Mitchell, Herbert S.

Pvt.

26

Sept., 18 near Fey-en-Haye

Neese, Paul M.

Sgt. 1Cl

5

Nov., 18 near Montigny

O’Quin, Sevan J.

Pfc.

20

Sept., 18 near Fey-en-Haye

Padgett, Elmer

Sgt.

17

Sept., 18 near Fey-en-Haye

Snyder, Harry 0.

Pfc.

1

Nov., 18 near Romagne

Swanson, John E.

Pvt.

1

Nov., 18 near Romagne

Weatherly, John W.

Pvt.

13

Sept., 18 near Fey-en-Haye

JARVIS J. BAIN, Colonel, Engineers, Commanding.

|

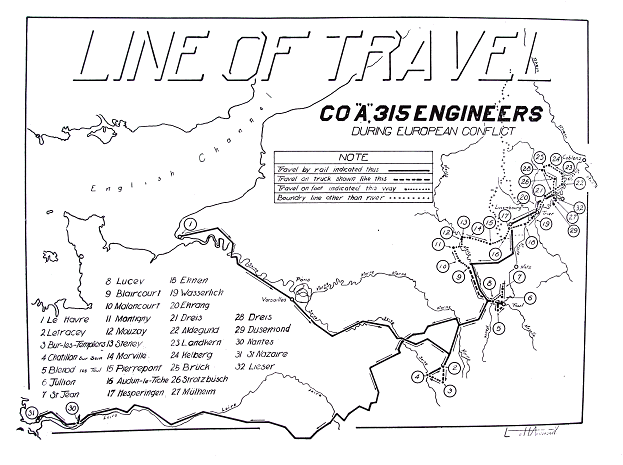

^&By Way of Explanation

In the next few pages you will get the story of our travels. For this interesting article we are

indebted to Captain J. E. L. Millender. Early during the period of our introduction to “Fritz” and his “G.

I. Cans,” it became known that Captain Millender had been writing a diary of our trip for his personal

use. While it had not always been possible to keep it entirely up to date, nevertheless, when opportunity

presented itself, and with the assistance of Sgt. “Pete” Odell, Captain Millender would “continue the

march” on this important document. Realizing that anything that the Captain might write would be

interesting, many members of the Company tried to make arrangements to get copies of the diary when

finished. This finally led to someone suggesting the publication of a book to commemorate our trials

and tribulations. You now hold in your hands the finished product.

We would call to your mind that the narrative you are about to “take a whack at” may appear

disconnected in spots. In passing out your condemnation or praise, kindly bear in mind that it was

written under all sorts of adversities. You will find the facts clearly stated. They have been presented in

a soldierly manner – exactly as we felt about things as they happened. In case you are timid, risk only

one eye at a time.

The Staff takes this means of expressing its appreciation of Captain Millender’s sincere efforts to

make our publication a genuine success.

|

|

The Way It Happened

BY

CAPTAIN J. E. L. MILLENDER

N September twelfth, nineteen-seventeen, the nucleus of the 90th Division was ordered to Camp

Travis, Texas, the South’s largest cantonment, and it was with great anxiety and enthusiasm that

we awaited the arrival of the first contingent of civilians called to the colors by the draft, and it

should be recorded that the men who a few days previous were civilians took hold of the new work with

great enthusiasm and loaned every effort toward the organization of the vast army as planned by the

War Department.

Our days here were spent in equipping the new arrivals and teaching them the intricate, yet

difficult, Infantry drill regulations. This, in itself, was one of the greatest experiences of our life in the

Army, for here we learned the rudiments of discipline and listened patiently to the teachings of our

superior officers who had seen previous service. We had gigantic schedules, for it must be remembered

that we were required to learn the work of the Infantry and master it as well as carry out our technical

studies and practices.

Sometime in May, nineteen-eighteen, we had begun to get wind that our Division would soon

move for a port of embarkation. As these rumors were quite prevalent at this particular time no one

seemed to lay much stress upon the so-called “latrine” gossip. To sum the situation up, we were really

glad of the news for we had been in training for a year at this cantonment, and it was work and drill from

hell to breakfast. On June third, we received our final orders for movement, and our Regiment was in

the first contingent which was to entrain for a port of embarkation.

On the morning of the fifth, at nine-thirty, we pulled out over the M., K. & T. for New York.

There were many things which happened en route, both pleasant and unpleasant. In the first place, the

Tourist sleepers were crowded, and the men had to sleep with discomfort. We stopped in St. Louis for

three or four hours, and the Red Cross was the grand institution that fed us on cakes, chewing gum,

cigarettes, etc.

At Mattoon, Illinois, the gang turned out for a general leg stretching. We paraded the town, but

everything was eyes right and eyes left. The town is full of pretty girls and the old boys, after having

ridden so far in the nice cattle cars were, indeed, glad of the opportunity. There were certain Sergeants,

as well as Lieutenants, whom the writer happens to know have excellent wives at home, who were seen

kissing the Mattoon girls as the train pulled out – of course, we are too proper to mention any names.

We could tell the minute we hit Arkansas because, upon passing farms and cultivated land, the

manhood of the State was to be seen seated with the utmost ease waiting for some squirrel to pop his

head out of a hole in some nearby tree, while the old lady and the barefooted kids acted as skipper for

the plow fleet. Conditions were a little better in Missouri, because we saw two or three men really at

work. Popular Bluff was quite an apple in our eyes, the natives were really “white folks.” The Regiment

was assembled and the Regimental Songs were rendered in an excellent manner.

We arrived in Indianapolis about dusk. After a two hours’ stay, during which we engaged in

callisthenic exercises, we pulled out for Cleveland. Cleveland was the first place in which we saw

O

|

|

women porters on Pullmans; this was really the first indication of our approach to the war industries;

women could be seen working in munitions factories, etc.

Upon arriving at Buffalo we saw a section gang composed of women working on the railroad

track. From Buffalo we went to Rochester and Rochester was the first Honest-to-God town that we

passed through. The inhabitants turned out en-masse to greet us, and we in turn paraded the town with

our band and sang for them. The Red Cross ladies were great! They supplied us with postal cards,

chewing gum, flowers and cigarettes. We are all strong for Rochester.

Our trip through the Catskill Mountains, and on down the Hudson, was a beautiful journey, and

the beauty of the mountains in the early morning while we passed through shall long be remembered.

The river craft were plying to and fro through the cascades and yonder toward the East ‘midst the first

rays of the morning sun could be seen the historic and beautiful West Point.

We arrived on the New Jersey side, took the ferry at Weehawken, went down the river, and

around the battery, beneath the five great bridges and landed on the Brooklyn side. From the ferry we

were transported to a point close to Garden City, thence to Camp Mills.

Of all the places, from the cold Yukon, so fervent in the memory of one Robert W. Service, to

the country once roamed by our old friend Stanley, this is the damdest spot for any government to put

any bunch of men for rest. They called it a rest camp, meaning you arrive at eleven o’clock p. m. and

work the rest of the night. It was raining, as always is the custom when soldiers have to move, and, in

spite of all the clothing we possessed, and could steal, we nearly froze. Texans and Oklahomans in New

York at this time of the year were entirely out of place. Some of us attempted a bath – to date we have

not thawed out. We were told we were to remain in Camp Mills for a week or ten days, but were ousted

out at two o’clock one morning when we had been there only forty-eight hours. This forty-eight hours

was spent in issuing Quartermaster property to the troops and no one had enough sleep to speak of. So

we left at two o’clock. We entrained at Garden City and proceeded to a point on the East River just

above the Brooklyn Navy Yard, transferred to the ferry and again we rounded the battery and up the

Hudson to Pier Fifty-seven, where we embarked on a British ship, the “Olympic.”

We were tired and hungry, and the embarkation was slow for us, and the worst of it was the

quarters we had for the men on board the ship. There was entirely too much distinction between the

Officers’ quarters and those of the Men, but, of course, we attribute this to the purpose for which the

ship was built—she was originally a passenger liner. We went on board the Olympic at eight o’clock on

the morning of June thirteenth. On the morning of the fourteenth at ten o’clock we cleared the pier and

told the old girl in the harbor “Good-bye.” At this time enemy submarines were active on our coast, in

fact, they had sunk five or six boats off Nantucket on the thirteenth, and it was no trouble to keep the

troops below. No one seemed to know where we were going, and we were without convoy. We regret

that the “Olympic” was so large, for the space available invited the General to issue orders for daily drill

to be held on board ship. Four times around the promenade deck was one mile. The 360th Infantry, two

Companies, namely A and B, of the 315th Engineers, a detachment of one hundred and fifty Marines,

two Companies of the Signal Corps, a Casual Detachment of Officers and Men, numbering about five

hundred and General Allen and his Staff constituted the passenger list. The weather was fine, and the

trip uneventful, so far as rough voyage was concerned and submarine attacks, and there was but little

sea-sickness.

On the morning of the twenty-first we sighted the coast of the Isle of Wight. We passed St.

Catherine’s Point and had a wonderful view of Cowes City, which is a most beautiful place nestled in

|

|

the hills of the seashore. This was at one time used as a summer resort for the German Emperor.

Further up the river we passed Osborne Castle, a noteworthy place, for, at one time, this was the home

of Queen Mary. Just before pulling into Southampton we viewed a spectacular fight between several

British destroyers and an enemy submarine. We docked at Southampton at 10 p. m., June twenty-first.

Disembarkation was begun at daylight, and this was our first real experience in the war zone. The docks

were loaded with munitions and guns of all description, British troops hurrying to and fro, hundreds of

steamers lying in the docks being loaded to cross the channel. We spent the day lying around the docks,

and, finally, about six p. m. we were loaded on a smaller ship, the “Archangel,” of seven thousand tons

displacement. We had nothing to eat all day long save bully beef and hard tack, and we were crowded

in this vessel like sardines. With a great convoy of British destroyers we started for Le Havre. The

channel was very rough and we had more cases of sea-sickness in the thirty or forty miles than we had

during the entire trip across the Atlantic.

Upon disembarkation at La Havre we proceeded to another rest camp. Here we brushed

shoulders with practically every kind of soldier in Europe – British, Scotch, French, Canadians,

Algerians, Italians, Australians – and, the most comical of all, the French territorials from Morocco –

Algerians. They look just like Texas negroes, but they do not parley English. A nigger soldier, a

member of one of our Engineers service Battalions, upon passing one of these Algerians, said: ‘Hello,

Niggah, how long have you been heah?” The Algerian stopped, looked at him and said: “No compre.” A

negro Sergeant further back down the line laughingly said: “Yeah, I guess you know when you is

noticed; that niggah done been ovah heah so long he got so high-falutin’ he won’t talk English no mo’.

‘These niggahs done got the swellhead.”

La Havre is truly a cosmopolitan city – with the enormous influx of troops, some going home on

leave, the majority en route to the front. One soldier in particular of this great cosmopolitan army

appealed to us in that he was an unique character, a Scotchman, a true Highlander, with his kilts and

paraphernalia of his clan. He had been with his Regiment, a bunch of Cameron Highlanders on the

recent offensive in Italy. He was one of several who were en route to the Highlands for recuperation.

He had been suffering with malaria, not being accustomed to the low marshy lands in the particular

territory of Italy where he had been campaigning. He was a forlorn looking creature, but the best part

about him was his smile. He carried a bucket about the size of an ordinary two-gallon pail. In this pail

he had some spare parts for his dress. We don’t know what they were, but we guessed at it. He also had

soap, sox, and a small wash tub. From his belt somewhere beneath the folds of his kilt there was

attached a rope about one inch in diameter and on the end of it, was a shaggy flea-bitten cur. The cur

didn’t savvy English, but he moved around when McPherson spoke. Upon the back of this odd person

was strapped a British pack full of God knows what. With his rifle slung over his shoulder, a wash pan

suspended from the bottom of the pack he presented, altogether, an appearance both amusing and

distinctive. All of his front teeth were missing. From this we concluded that, being a true Scotchman,

he had worn his teeth out biting necks off of Scotch whiskey bottles. Even at that, he was happy and

contented. He handed us a blarney that was interesting – he had soldiered four years and a half as was

evidenced by the red and blue chevrons on his sleeve.

We were accorded many courtesies at this place, but we cannot say much for the rest camp. We

consider them quite a joke. No one rests. But still they afford an opportunity to quench one’s thirst.

They have an enormous supply of good beer and wine. They issued nice blankets, seemingly made of

Porcupine hair intermingled with cactus – which would have made mighty good beds for horned frogs,

but we couldn’t say much for them for soldiers. They might have been all right if we had had a pair of

scissors to clip them, but they sure did stick. We didn’t grumble when they said, “Turn them in.”

|

|

We suddenly got orders to entrain for parts unknown – nobody knew where we were going, not

even the railway transportation officer. We had a jolly time just before entraining as a group of Scotch

soldiers, keenly alive with good Scotch whiskey, sang several Scotch songs, and some of our boys still

more alive with various brands sang any and every old thing. We hiked about six miles through the dark

– it is remembered that on account of aerial raids the cities are without lights – through rat holes, up and

down alleys, a regular bunch of alley rats, to a railway station.

We were loaded into cars in a worse manner than cattle could be loaded, forty-six men to the car.

Incidentally, the French box cars do not compare favorably with any other vehicle on earth. They

resemble a cracker box or a bird cage on rollers. They only have four wheels, whereas they need a

hundred to make them comfortable. One good American locomotive could pull a thousand of them. We

pulled out at 23:47 o’clock for God knows where, and nobody “gave a damn.”

The night on that train was some night. Nothing to eat save corned willy and crackers, so hard

that they couldn’t be cracked. By the time daylight overtook us we were just about as sore as a fat

woman with a busted corset string. Sleep? Hell! You couldn’t even sit down – we were lucky we didn’t

fall out of the door. If you reached down to scratch your own leg you would be pulling some other

fellow’s hair. Cooties? No! There was no room for them in that gang. We were just as crowded as a

stomach full of dried apples after drinking water. We traveled at the magnificent speed of a kilometer

every now and then. The slow train through Arkansas was a lightning express compared to this outfit –

it would make us look like we were backing up. There was one thing in our favor, however, we could

see the country; in fact, we passed the same point several times. We saw one old man raise an Irish

potato crop as we whisked by. We noticed that every foot of ground, valleys, hilltops and all, were

under cultivation. We passed close enough to Paris to see the Eiffel Tower. At some place along here

we were met by several girls of the French Red Cross who dished out a sort of bouillon that tasted like

Octagon Soap, but wine was plentiful and Cognac more so, so we didn’t care whether we had anything

to eat or not.

After having ridden for twenty-four hours we were unloaded in some God-forsaken place. They

call it “La Trecey,” meaning “The Trace.” Rightfully named, for all that remained of this burg was a

mere trace. We had not the least idea of our latitude and longitude. We were hungry, cold and tired,

and, to dishearten the entire gang, echoes of heavy cannonading were heard toward the East. We knew

not our proximity to the front, and at daylight we discovered that we were lost – put off at the wrong

station. We carried water for a mile and half and lived on hard tack and corned beef.

The French have a wonderful refrigerating plant, in the form of a stream, about six miles from

this camp. We tried it once and the survivors have not bathed since. Upon emerging from this water,

our pals had to beat the ice off with sticks, that is, those of us who were not frozen too stiff to wield a

stick. We stayed in La Trecey eight days, trying our best to locate someone who could inform us of our

whereabouts, or our final destination. Our Division had not arrived in France.

Finally we were directed to proceed to another God-forsaken place called Bure Les Templiers.

This town was built by the sires of Caesar, and here we became acquainted with the typical French

billet. These billets are great, more than that – they are glorious, that is, if one can succeed in scraping

enough cow manure away to find the billet. A French peasant’s wealth is computed from the size of the

manure pile adjacent to his kitchen door. They wear wooden shoes, and it is amusing, indeed, to see

them plying through the streets in these queer little boats. They steam up to their back doors through the

liquid manure, disembark and leave the wooden shoes at the steps. This was the first time American

|

|

troops had entered this town and all of the girls turned out to meet us. She was a beautiful maiden of the

vintage of 1812. She didn’t parley English, and we didn’t parley her stuff.

The French farming system is different from ours in this respect: The farmers do not live upon

their farms, they live in one central point which is one of these villages, and, using this as a radical point,

they go to their farms daily, driving their stock, etc., to their particular plots of ground. From

Napoleonic times the live stock has been trained in the conservation of excreta, and efficiency is their

watchword. Thus we derive the why and the wherefore of the filthy condition of the village streets.

Some system! The old ladies sewing circle serve as white wings in the conservation of the fertilizer.

They know as much about sanitation as a monkey does about a munitions factory. This town, Bure-les-

Templiers, is an historic oasis, as the church was built in the eleventh century by the Crusaders. We

remained in this town from the second day of July until the nineteenth of August, when we received

orders to move to parts closer to the front.

Bure-les-Templiers was known as the intensive training area for fresh arrivals from the United

States, and our Regiment having received, just prior to leaving the United States, a bunch of recruits

from Camp Dodge, Iowa, we were forced to carry out an extensive drill schedule.

For a period of six weeks we had four hours of Infantry drill each morning and each afternoon

was spent in bridge building, erection of barbed wire entanglements, shooting on the target range, and

practice in hand-grenade throwing. At times the schedule was varied in that we would have held

maneuvers to practice in the capturing of enemy strong-points, and also during this period night

exercises were thrust upon us in order that we might learn the erection of barbed wire entanglements in

the dark. Twice each week the Regiment, with full packs, had to hike fifteen kilometers and, for

disciplinary purposes, each man was allowed one canteen of water. We also began wearing our gas

masks five minutes at a time on these hikes, and at the end of a few weeks we had worked up to the

point where we could wear the mask one hour without removing.

Here we were issued spiral puttees, overseas caps, steel helmets and were introduced to the

hobnail express. Events happened with lightning-like rapidity. We were issued French horses, escort

wagons, engineering equipment, gas masks, and our old Colonel had told us that as soon as we began to

receive our equipment, then we might know that we were scheduled for an early tour of duty in the front

line trenches. How true his prophecy was! For no sooner had we been equipped than we were ordered to

entrain at Chatillon sur Seine.

From Bure les Templiers the Regiment hiked to Chatillon sur Seine, a distance of thirty-three

kilometers, or about twenty miles. This distance was covered in one day, and, with full equipment. It

made an exceedingly interesting hike. Upon our arrival at Chatillon sur Seine, we entrained in the

customary “Hommes 40, Chevaux 8.” and proceeded to Don Germain, a wee village near Toul,

detraining at this point and marching the five kilometers to Blenod la Toul. We were billeted here and

remained for a purposed rest of two days, but during this period we were busy checking over our

Regiment, cleaning accouterment and making preparations for our tour of duty in the front line trenches.

We proceeded to a town named Jaillon, moving by night in a truck train and, on account of the

liability of air raids and the usual nightly excursions of German bombing planes, vehicles traveled on the

main highways with fifty meter intervals between trucks. We did not have animal transportation to draw

all of our escort wagons and rolling kitchens, and this, of course, necessitated towing the escort wagons

behind the trucks, and, after having traveled a few miles, the convoy was held up on account of hot

bearings on the wagons.

|

|

Jaillon had been under enemy shell fire for many days, and, inasmuch as we had not been under

fire, we entertained great anxiety relative to the subsequent experiences which we were to have within a

few hours.

Everything moved in darkness. We were not allowed to smoke nor strike matches nor have

flashlights, and, were it not for the fact that the highways of France were constructed of limestone

principally, travel by night without lights would have been very difficult and quite a serious problem on

account of the immense amount of the two-way traffic, but the white roadways in the darkness

facilitated travel immensely.

Upon arriving at Jaillon we repaired to a nearby wood, under which we secured cover from

enemy aerial observation, completing our bivouac just before break of day. We lay in hiding throughout

the day, allowing only a few men at a time to move from the cover of the trees to the company kitchen

which was hidden in a demolished stone building.

With the fall of darkness, we slung our packs and proceeded further toward the front by way of

Domevre and Martincourt to the small village of St. Jean. Little did we know at this time the

significance of St. Jean and the immense lessons which we were to learn on this, our first trip into the

fighting lines. This march was made in a column of twos, with one hundred meters between platoons.

We were met at St. Jean by our advance party whom we had sent to the front twenty-four hours

previously to familiarize themselves with the lay of the land and facilitate our relieving the troops who

were then in the line. We relieved the First Engineers of the First Division on the second line position in

what is known as the Villers-en-Haye Sector.

By daylight we were housed in a system of splinter proofs, resembling the dwellings of the Cliff

Dwellers’ class of architecture. They were not half bad as they had electric lights and were situated on

the side of a beautifully wooded hill overlooking a picturesque little valley, near the bottom of which lay

the town of St. Jean.

Well, sir, of all the nightmares that a man could possibly have in one lifetime my experience

upon my first arrival at the front will outclass anything that could possibly happen in many years of an

ordinary life. We had been on the move for several days, and we were as tired as hell, and hungry, and,

after hiking about twenty or thirty miles, we moved into a place called St. Jean, situated in a beautiful

little valley, and this was no lie, because it was a beautiful little valley, nice pine trees and fir trees

clustered here and there around the hills, pretty winding macadamized roads and one of France’s famous

cold water streams winding its way slowly southward. This valley was situated on the second line of

posts in the Toul Sector and outside of bombardment periodically from the German guns, was an ideal

camp. We pulled into this place about two o’clock one morning completely fatigued. The men

occupied splinter-proof shelters, which, in spite of the rats and cooties, was a pretty good place. Being a

smart kind of a guy and my first trip into the trenches, I didn’t much like the idea of flopping in the

particular shelter which was assigned to me for quarters, so I made my bunk in a ration cart on a side of

the hill. My faithful old Top Sergeant, never forgetting his duties, had posted the necessary gas guards,

this from force of habit more than necessity. I was awakened with a start just before daylight, and,

arising, half asleep, peered over the side of the ration cart to ascertain the cause of the disturbance, and

there, within two feet of my face, peering at me like a devil, was some object which at first I could not

make out. The thing was mumbling to me in low tones which I could not understand. I grabbed my six-

shooter first and in my fright I almost fired when, suddenly, it dawned upon me that it was a gas guard.

I will tell you right now that was a fearful looking object, that man with a gas mask over his face and

|

|

yelling frantically for me to get my gas mask on and me half asleep unable to comprehend the situation.

Finally it dawned upon me that there was a gas attack; and then began the wild scramble for my gas

mask. In the meantime, I was holding my breath to keep from breathing the deadly fumes, and, the

more I hunted, the less I found. When, finally, I was about to burst for the want of air, I located the

damned mask and got the tube in my mouth long enough to draw a breath. After adjusting my mask, I

looked out over the valley and beheld a heavy white cloud, whereupon I thought: “My God! the

Germans have put over a gas attack at high concentration.” And I wondered if my Company had been

wiped off the map. I wondered if they had been warned by the gas sentry. About this time I was wide

awake to be sure and thought I would test for gas to determine its concentration, and whether or not it

was chlorine or what the hell. I couldn’t smell anything, so I took off my mask, got out of the cart and

smelled all around and finally decided that it was nothing but a fog.

And so it goes – fortunes of war. There wasn’t enough gas to kill anything; in fact, there had

been no gas attack launched – no bombardment.

Our only trouble at St. Jean was spasmodic shelling three or four times a day from the German

batteries. We had been told by the Engineers whom we relieved that this was a quiet sector, but the first

day in camp the Huns threw into our area more than a thousand shells, mostly high explosive seventy-

sevens and Mustard gas.

During the day the men were forced to keep under cover on account of direct enemy observation

from observation balloons and aëroplanes. We proceeded to our work through groves and trees and

were quite particular in camouflaging our roads and pathways over which we carried materials that were

used in construction of combat positions. During the day we did not allow vehicles to approach our

camp, nor did we haul wood or water, this being left until after nightfall when we could move without

being seen.

We witnessed many fights between enemy aëroplanes and our own. The enemy, at this time,

were particularly strong on observation and reconnaissance work, and we found that, when we had

advanced during our attack of September twelfth, upon capturing a German artillery position, they had

excellent pictures of the entire area around Martincourt, and particularly the camp in which we were

billeted was marked on the German artillery charts which shows that, had they wished, they could have

shelled our camp off the map. It was almost a daily occurrence for the enemy to come over and shoot

down sausage balloons which were anchored in the vicinity of Martincourt. The strange thing to us was

that it seemed that when the Germans were on patrol work in the air we seldom saw any Allied planes

and vice-versa, when the Allied planes predominated one seldom saw German planes, but there were

many times when they did make contact and invariably a spectacular aerial battle was the result.

The relief was affected, and we took over the second line position, and carried on the work of the

construction of combat groups, strong points, dugouts, pillboxes, barbed wire entanglements and also

aided the artillery in preparing positions for the big naval guns of the Sixty-first Coast Artillery.

About four o’clock in the afternoon of September the eleventh, we received orders to move

forward and occupy the support trench immediately in the rear of the assaulting waves of the 357th

Infantry. Under full pack we labored over the shell-torn roads past innumerable artillery emplacements

of all caliber, slowly wending our way toward the long-since German-battered town of Mamey.

Everything was moving, dark as pitch, cold, and one of those old slow Texas drizzly rains. No

lights could be shown as the enemy lay just to the north in his front line positions about three kilometers

|

|

distant. We entered a communicating trench leading north from Mamey, and, of all the trenches that

ever existed since Jacob built the ladder, this trench was the roughest, darkest, wettest, nastiest and “By

Goddest” trench that any man in any army at any age, including Caesar and Methuselah, ever “did dam

see.” Stygian blackness would appear as an Aurora Borealis compared to the damnable darkness in these

underground regions as we poor devils trudged along cussing everybody in Germany at each breath.

Our load could be likened to the immense shells on the poor little snail’s back and, indeed, our gait

seemed many times slower.

We fell in holes, bumped into rocks, banged our heads on trench bridges, snagged ourselves on

barbed wire and, at one place, after we had laboriously negotiated seemingly innumerable miles, we fell

over what seemed to us a submarine. This proved to be a tank which had skidded into the trench

sideways. We started again, wet as frogs, and madder than nine kinds of hell, until we decided we were

lost.

From stumbling over rocks our feet were so sore that they seemed to be bleeding. To add to the

pleasantness of the situation, the rain continued harder. God was with us, but the Kaiser controlled the

elements.

After added prowling around, and stumbling over everything on earth, we located an old dugout

into which we filed to escape the drenching downpour. This dugout was an unique mansion in itself,

wet, musty, cold, and smelled like old socks. We arrived at this place at 12:15 a. m., September twelfth,

nineteen-eighteen, concluding a six hours’ combat between what at one time were good feet and the

hell-fired rocks of France. We had been stumbling blindly forward, not knowing our mission other than

the fact that we were to take up this position. No one was cognizant that an attack was to be made, nor

did we know the zero hour, but while en route to this position we had passed a great many tanks moving

forward. We knew from this preparation that the attack was coming before dawn.

We have read of the destruction wrought by Vesuvius, of the great San Francisco earthquake,

and of the so-called drum fire of thousands of pieces of artillery in action, but at 1:15 o’clock these

historical facts were as naught. Every piece of artillery in the St. Mihiel Sector, from Pont au Mousson

to a point fifty miles northwest, opened up simultaneously for the artillery preparation preceding the

“Over the Top.” The roar was deafening, the skies were lighted as far as the eye could reach in any

direction, and the whistling of shells of all calibers screaming through the air could be compared only to

falling meteors.

The particular dugout in which we were sheltered had thirty feet head cover, yet the vibration of

the detonations could be felt quite distinctly in our bunks. This intense roar of drum fire lasted until

daylight, when we gathered enough courage to venture outside.

Upon emerging we found that the assaulting Infantry had gone over the top at five o’clock

toward the enemy lines, and the artillerymen to our rear, a distance of a hundred yards, were clamoring

and yelling preparatory to moving up. At this time we received orders from our Major to cut the barbed

wire entanglements and clear the roads forward for the advance of the artillery. We moved out towards

No Man’s Land as far as the old city of Fey-en-Haye. This town had been in No Man’s Land for more

than four years, and one can imagine after four years bombardment to what extent the town was fit for

habitation. We found the enemy had barricaded the principal thoroughfares and built a veritable

defensive system of trenches and barbed wire entanglements.

|

|

Glancing into a trench paralleling one of these streets we saw three of our poor boys who had

been hit by a high explosive seventy-seven – a gruesome sight indeed, with their bodies mutilated

beyond recognition and brains scattered and hanging by bits on the barbed wire entanglements, legs and

arms blown entirely free from the body and the remains catapulted into the mire. Yet they carried the

flag over the top and ran the Hun out of his lair. They had paid the price.

From this point as we worked forward building a road, we could see scattered here and there

across the battlefield bodies of our own men and of the enemy. We saw, among other things, that the

troops opposite us consisted of Austrians and the famous Prussian Guards. They all looked the same to

these old Texans and Oklahomans for they bombed hell out of them just the same.

It was broad daylight now, and we perceived in the immediate foreground twenty-two airplanes

which we thought to be ours. Intense machine gun fire was heard, and we saw the twenty-two planes

split up into squads of seven each, and that one of these squads was in combat with another plane at an

elevation of about three thousand feet. After much firing, the lone plane was seen to careen and

apparently the pilot had lost control. We thought he was a German, the beastly devil, and great cheers

arose from the throng for we were witnessing the first downfall of a German pilot. As the machine fell

it turned on its side, both wings and the fuselage ripped and came apart and the motor, with the pilot and

gunner, fell to the earth. Much to our surprise and our sorrow we learned that the defeated one was an

American machine and had been destroyed by the famous “Flying Circus” – Germany’s crack gang of

aerial cutthroats.

These devils infested the air, harassed the troops with aerial machine gun fire, and completely

controlled the skies during the entire advance of our Infantry. They never split up, the cowards, they

work in gangs. They are all aces and visit back and forth along the entire German front. The machines

are painted all sorts of gaudy colors – red, white and black – from which they obtained the name of “The

Circus,” and were organized by the German ace, Baron von Richtofen.

By ten o’clock our Infantry had advanced seven kilometers, over four miles, through what is

called the “Stumpflager,” a place infested with machine gun nests, trench mortars and endless seas of

barbed wire entanglements. The edge of the woods on the side from which we attacked was on the

military crest of a hill lending every advantage to the intrenched enemy. The woods followed back to

the north into a ditch or wide deep ravine in the form of a Y, and this ravine was strongly fortified as it

had been the rendezvous of the henchmen of Kultur and the Potsdam gang for four years.

They had excellent dugouts of concrete. Their machine gun nests, strong-points and combat

groups were magnificent in construction and position, but our brave boys waded into them, flanked them

and killed them like rats. Our heaviest casualties were in the fight in this wood, for, incidentally, it is a

man’s job to clean out machine gun nests. There were twenty-eight of these machine gun nests

destroyed and their gunners were routed or killed at their posts, and here again the fiendish devils were

found to fire hundreds of rounds of ammunition at our boys and, when the supply had been exhausted,

hold up their hands and cry “Kamerad.” Little good did the “Kamerad” do, a hand grenade finished

him.

As soon as the attack opened, hundreds of prisoners were to be seen under guard filing slowly to

the rear, many of them carrying our wounded. We made them bury their own dead and so forth.

We labored throughout the day filling shell holes, trenches, clearing barbed wire entanglements

and opening lines of communication. One platoon under command of Lieutenant P. M. Nicolett,

|

|

trudged incessantly to and from the ammunition dumps carrying ammunition to the Infantry advancing

waves. When the roads had been repaired sufficiently the entire Company carried on the work of getting

ammunition forward. We labored like dogs without food, water or rest all day and throughout the night

and continued for sixty hours. We labored without murmur, tired, hungry, wet, sleepy, but no one gave

a darn, because the Germans were on the run.

Our troops were victorious, had gained their objective and three kilometers further. One

company of Infantry advanced through our own barrage to a hill two kilometers in advance of the

barrage zone, but they were Americans and, instead of fighting their way back, they fought on, driving

the Hun before them, and, as a result when the attack ceased, these men had the outpost line established.

The German stronghold known as the “Stumpflager” was indeed a sight which can only be

revealed by sudden calamities – earthquakes, battles and preeminently a surprise attack upon an enemy

resulting in their defeat and rapid retreat. They left everything under the sun – horses, wagons, tailor

shops, blacksmith shops, boot shops, ammunition depots, engineer dumps, hospitals, guns, food,

clothing, kitchens, wine, beer – in fact, everything that an army of the German character can carry in the

field.

Our Company moved into what twelve hours previously had been the quarters of a German

Colonel and his regiment. Inasmuch as we found potatoes, cheese, bread, etc., together with the coffee

carried in our men’s condiment cans, we prepared what was to us a nice meal. Immediately our boys

could be seen with every kind of souvenir that hands could pick up. We slept on German blankets,

traded our wet shoes for nice dry German shoes; any number of our boys had German pistols, overcoats,

belts, bayonets and various trinkets too numerous to mention.

Our Company salvaged eight machine guns, six trench mortars, fifty thousand rounds of

ammunition. We immediately set up the machine guns as anti-aircraft weapons to shoot at the “Circus.”

A Medico from our detachment found a lovely fountain pen lying on a table in a dugout. He picked it

up and upon unscrewing the cap met a disastrous explosion. He was wounded, perhaps fatally, another

trick of Kultur. Still, another man in exploring these dugouts in quest of souvenirs in company with

several men from this Company found a safety razor. He picked it up, opened the lid, and it thankfully

shot off one hand. These are two of the many traps we have found in the existing German positions.

The fighting further ahead by this time had subsided materially, and all that remained was a

continuous duel between the artillery. Here and there could be heard bursts of machine gun fire and

detonations of hand grenades by mopping-up parties. Part of our outfit had gone ahead to the newly-

made objective and were busily engaged in organization of the terrain, laying out strong-points for the

Infantry to dig in while the rest of our Company was busily engaged in carrying ammunition and tools

forward for the Infantry and barbed wire for making entanglements.

Indeed, many heart-touching scenes were encountered during these hours. While passing

through the woods we heard moans from the darkness, and investigation revealed six or eight of our

boys who had been wounded and had been lying on the battlefield since early that morning awaiting

evacuation. Their wounds were painful and the night was cold, and still it rained, but they did not ask

for comfort. They wanted water and to kill the Germans.

About dusk, after we had gotten located in the captured enemy positions we were subjected to

heavy shell fire from the north. One of our boys, Private Weatherly, was hit by a splinter from a high

explosive shell, this being our first casualty in action.

|

|

The following days revealed many incidents, both sad and amusing. We contented ourselves,

though we had nothing to eat save bully beef and hard tack, with scouring the woods, getting material

forward, searching newly captured dugouts and artillery emplacements. We found one machine gun

which had been held to the last minute. Lying upon the piece was a German, apparently more than fifty

years of age, who had been killed while feeding these fiendish death dealing weapons. About twenty

yards distant lay the body of an American. It was apparent that, though mortally wounded by this

machine gun, this boy had carried out his mission, killed the machine gunner and put the gun out of

action. He died with his head towards Germany.

We found extensive engineer dumps, a Decauville railroad system and two German locomotives

which were soon put into service hauling materials forward. This brings the Company in general up to

the final stage of the action, wherein the front lines of our troops were consolidated and our unit divided

into distinct groups with more or less distinct duties. Many interesting and exciting incidents occurred

from now on, but pertain to these individual units of our organization.

At this stage of the advance our lines had engulfed several important villages which were a few

hours previous German territory. Refugees arriving gave information of enemy positions and a

particularly large munitions dump two or three kilometers in advance of our outpost positions, and,

indeed, in territory yet unexplored by our patrols. Incidentally, this dump was located within three

hundred meters of the Hindenburg line, in the vicinity northwest of Preny, to which positions the

Germans had retreated, strategically strengthening their lines and organizing new combat groups. It was

the desire of the Army Commander that this munitions dump be destroyed. It was not definitely located

on existing maps. Our aerial activity was limited on account of air superiority caused by the presence of

the “Flying Circus,” and, therefore, our artillery could not destroy the dump.

Engineers were called upon to reconnoiter because they, as specialists, could definitely locate the

point by co-ordinates, and for this arduous undertaking Lieutenant Nicolett was detailed. His detail

consisted of the following men: Sgt. James C. Duke, Corporals Frank M. Duckworth and Charles M.

Harrison and Privates Albert Doglio, Rubie Wimberly, Jasper B. Knox, David J. Williams and Clifford

E. Wilkie. As a protective measure, there was assigned to him a patrol of one Lieutenant and fifty men

from the Infantry Brigade. A guide was furnished by the Infantry, as they had patrolled most of the

forward areas.

As is customary, the guide became lost and our detail wandered in the woods the entire night.

With dawn came the Engineer’s intuition of aggressiveness and self-reliance. Lieutenant Nicolett

assumed command of the party and proceeded to locate the supposed point on his own initiative. Upon

emerging from a wood he, with his detail, started across a well defined road. One of the Infantrymen

cried: “Down, Lieutenant! Look over there at your right!” Fifty yards distant there sat two Germans in

front of a dugout who, apparently were on outpost duty from their lines, and, luckily, Lieutenant Nicolett

was not discovered.

Our party crept past these guards for four hundred meters and succeeded in locating the enemy

positions and a dump containing vast quantities of explosives, shells, small arms ammunition, lumber,

Decauville track sections, frogs, switches and large quantities of giant shells known among Americans

as “G. I. cans.”

Upon exploring nearby dugouts containing ammunition the dump was found to be mined by the

enemy, electric wires leading back to the enemy lines. Our boys succeeded in placing eight large

|

|

charges of triton among the other explosives, proper arrangements were made for the retreat of the

detail, the word was given and the fuses were lighted.

As the party retreated they were forced to emerge from the woods into an opening. This

exposure drew enemy machine gun fire, several Germans appeared in a small system of trenches fifty or

seventy-five yards to the right. Our party deployed as skirmishers and engaged the patrol in combat;

two Germans were killed outright and our party lost one man killed and one wounded. No sooner had

our party cleared the vicinity of the dump when the enemy opened fire with artillery. Our boys safely

escaped the barrage, returning to our lines at two o’clock in the afternoon.

Speaking of rats – they have the most complete organization in the trenches today. Their

organization is wonderful. Their strategy makes Hindenburg a regular sideshow. They have Brigadiers,

in fact, they have rats in this army some of which wear six or eight service stripes, iron crosses and

everything.

When you come plodding along the trench with mud up to your knees stumbling over the rocks

you will find these rats building pontoon bridges. They stand up and salute just as smart. We saw one

big gray backed devil about sixty years old wearing a German helmet. You hear them coming around

corners of a trench and you think it is a German. They have guard mount, and all kinds of formations.

We can’t tell which is the worst – rats, cooties or fleas. We can’t tell just how big the fleas are, because

no one yet who has encountered one face to face has ever lived long enough to describe him. We know,

though, that they have bullet-proof hides because a forty-five won’t kill them.

To alleviate the soldiers who have been occupying the trenches for some days they have a nice

dipping vat arranged where you strip off your clothes and wade through the vat just like a bunch of

cows, same as we used to do on the Capote Ranch. Here is where you put the gas attack to the vermin

and emerge a clean man. They give you nice clean underwear that has been fumigated and you return

again to the trenches.

Our dinner on the evening of September twentieth was a memorable affair. We had several most

distinguished visitors who dropped in upon us unexpectedly. Some of the Kaiser’s damned kinfolks in

the form of seventy-seven high explosives. They were characteristically German. It was an excellent

meal we had begun. The first one burst about a hundred feet south of the kitchen, the second one

followed about two or three seconds, forty feet away, but the chow line was all safe. Our bugler,

Gersch, said that he dived into a hole about 4x4 in dimension, occupied by thirty men, and there was

plenty of room. Somehow, before these things came over we had been discussing shells and shell fire

and Germans and Hell fire, among other things, saying that a man who claimed he was not afraid of

them was an unsophisticated liar.